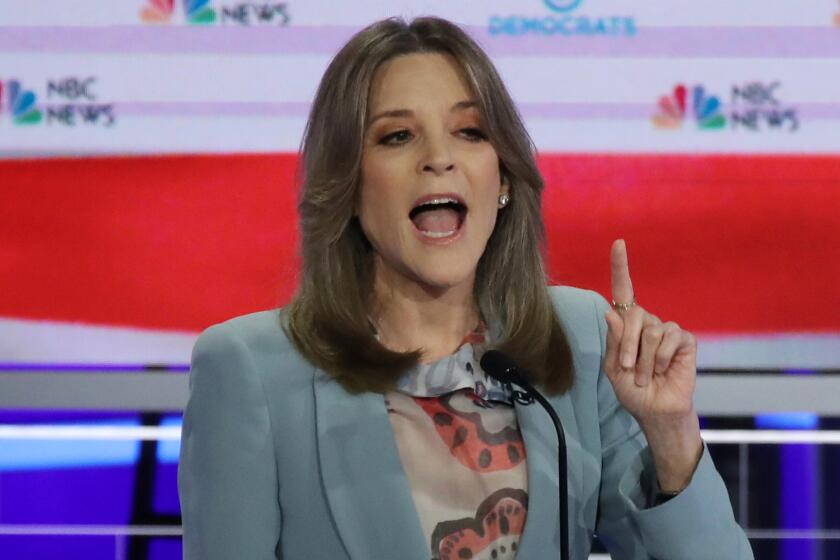

Oprah’s ‘spiritual guru,’ a longtime Californian, tests whether new age can win votes in New Hampshire

Presidential long shot Marianne Williamson flitted down the aisle of a two-century-old granite church, pausing to gracefully bow to dozens of supporters as they chanted her name.

The author, the most well-known Democrat who will appear on the ballot Tuesday, when New Hampshire holds the nation’s first presidential primary, spent much of her adult life in Los Angeles before moving east in 2018.

Williamson, who has never held elected office but was once dubbed Oprah Winfrey’s spiritual guru, has next to zero chance of denying President Biden his renomination. Polls suggest that many New Hampshire voters may write in Biden, who will not appear on the ballot after the Democratic Party chose to revoke the state’s first-in-the-nation status and make South Carolina the first official primary.

But Williamson’s quixotic second bid for the White House (she also ran in 2020) is a test of a different question: Exactly how many of these supposedly flinty New Hampshirites will vote for a woman who has been stereotyped as a “woo woo” Californian?

The Texas native’s ties to California date back decades. In 1970, she moved to California to attend Pomona College, where she studied theater and philosophy and protested the Vietnam War before dropping out a couple of years later. After bouncing around the nation and being sidetracked by what Entertainment Weekly called “bad boys and good dope,” she moved to L.A. in 1983 and shared an apartment with actress Laura Dern.

California Rep. Ro Khanna made the rounds in New Hampshire this weekend, stumping for a President Biden write-in campaign ahead of Tuesday’s primary.

Williamson, 71, became a spiritual leader and wrote more than a dozen books, one of which Winfrey promoted by saying, “I have never been more moved by a book than I am by this one.” Millions have bought her books, and she was adored by celebrities, officiating the 1991 wedding of Elizabeth Taylor and Larry Fortensky at Michael Jackson’s Neverland Ranch.

Williamson was also actively engaged in charities that helped those with HIV or living in poverty.

She came to believe that the two-party system disenfranchises the average voter by prioritizing the interests of wealthy elites.

“The majority of Americans are demonstrably a little bit left of center,” Williamson told The Times in an interview last year. “The problem is that we have a political system which is more beholden to the short-term profits of their corporate donors than to the will of their own constituents. Their idea of an acceptable candidate is someone who will perpetuate the system as it is. What we need in a president is someone who will disrupt that system.”

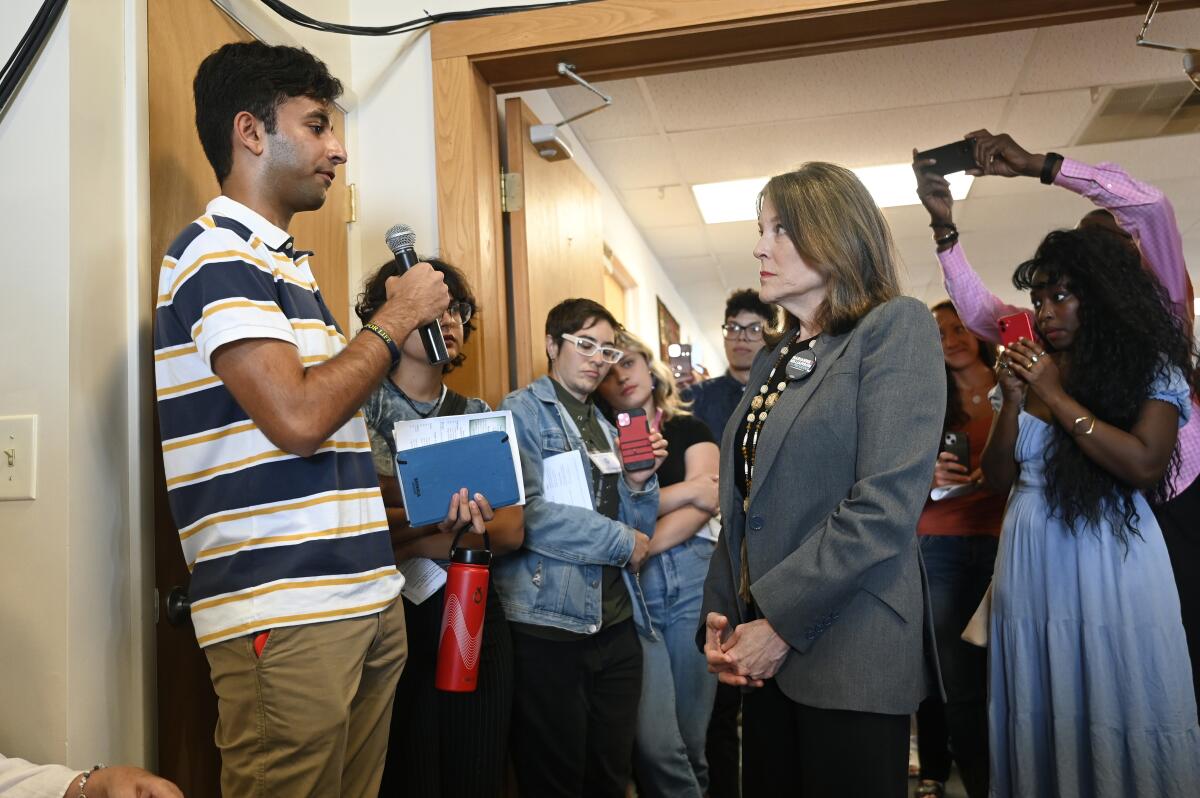

Williamson’s message resonates with a diverse group, but especially with people who believe that changing the system starts with changing oneself. Her followers include fans of her books, disillusioned Democrats and some former Bernie Sanders supporters.

But not many are New Hampshire voters.

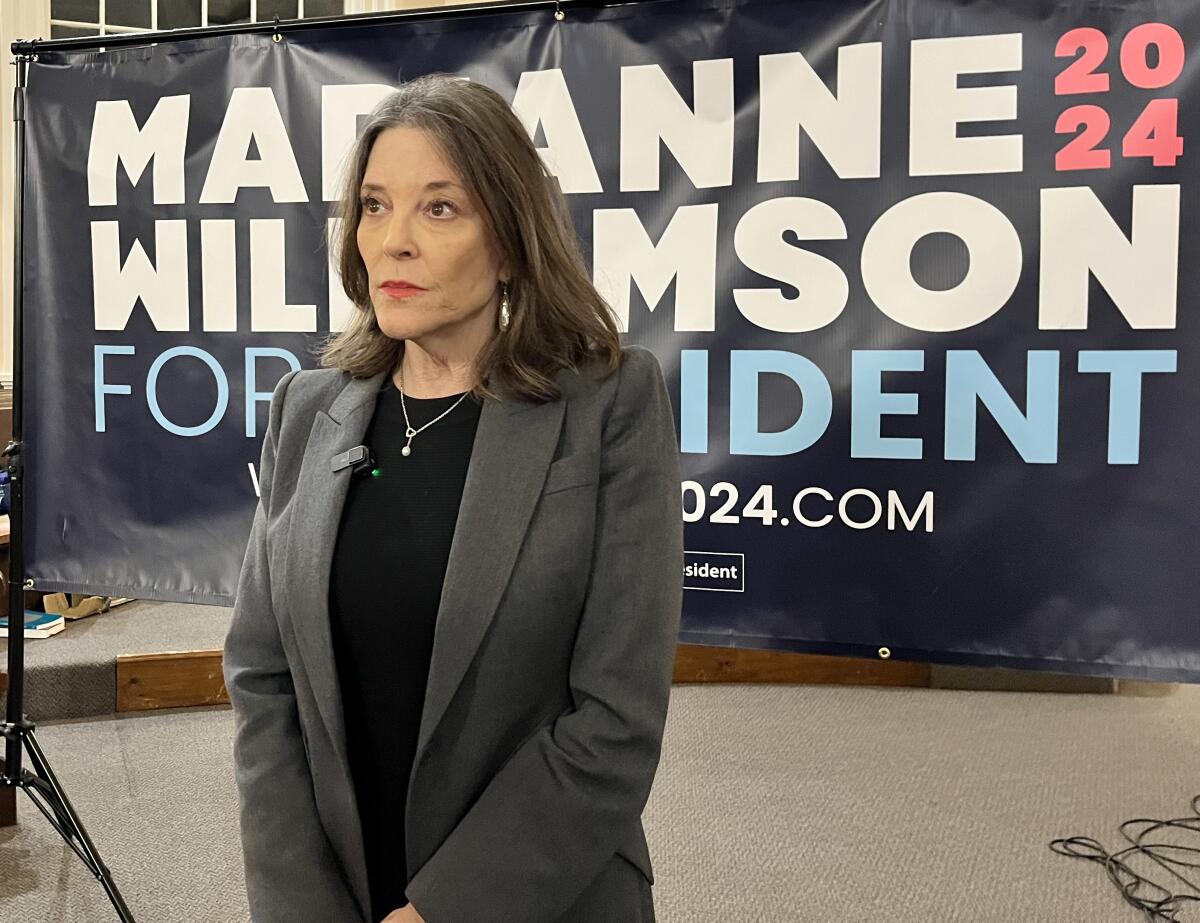

When she arrived this weekend at South Church Unitarian Universalist in Portsmouth, the pews were filled with nearly as many volunteers as voters.

Orson Maazel drove from rural Virginia to volunteer for the campaign. Wearing a “Disrupt the corrupt” sweatshirt, he said he was drawn to Williamson because she’s an outsider who doesn’t take money from corporations.

“I agree with her that we don’t just need people who got us into the climate mess we’re in and economic mess we’re in to get us out of the system,” Maazel, 35, said. “We need somebody outside who’s not bought by anybody and who has a really good character.”

Southern California has long drawn prophets and gurus, providing a fertile breeding ground for all manner of cultists, mystics and new religious movements.

Williamson brought tears to the eyes of Nicole Dillon, 47, who lives in Massachusetts. Dillon, who hadn’t known much of Williamson before the event, said she loved the candidate’s message about advocating for women and children, ending the war on drugs and combating climate change.

Dillon watched closely when, about 20 minutes into Williamson’s stump speech, a man approached the stage and took the candidate’s hand, quietly thanking her. The 50 or so people seated in the pews watched in uneasy silence until a couple of security guards approached the man to usher him off the stage.

“Can you just sit down for me now?” Williamson said softly to the man.

He turned around, noticed the crowd in the pews and, with a look of surprise, allowed security to usher him up the aisle, apologizing for the disruption.

“Just tripping on his birthday,” a guard said, shrugging and laughing, after leading the man out. “She draws all kinds!”

“He was drawn to her truth and her light,” Dillon said. “She was so gentle with him and like a mother. She’s very motherly; she’s gonna gather us all in her basket and take care of us.”

But neither Dillon nor Maazel can vote in New Hampshire’s primary.

Only 2% of New Hampshire’s registered Democratic voters said they planned to vote for Williamson, compared with 64% who planned to write in Biden’s name, according to a recent Suffolk University poll.

“She has a perspective that actually reaches a certain percentage of the population. The issue is, was that ever going to be enough to catch on nationally?” said Ray Buckley, chairman of the New Hampshire Democratic Party. “I don’t know anyone that doesn’t think she’s a good person. She’s in it for the right reasons. She just doesn’t seem to be connecting with enough voters to be able to be successful.”

Perhaps the inability to connect with voters comes in part from her unusual political presence. Williamson peppered her speech with $20 words, book titles and quotes. Her answers to voters’ questions frequently invoked references to books she had read, and sometimes an esoteric history lesson.

She repeatedly voiced frustration with the Democratic National Committee’s dismissal of her campaign. In several states — including North Carolina, Florida and Tennessee — Biden will be the only Democratic candidate on the ballot.

Should something happen to the president to prevent him from running for a second term, “I suppose their idea would be to put [California Gov.] Gavin Newsom ...” she said, before catching herself. “I don’t know. I don’t know any more than the next person does.”

Tables at the entrance laden with “Marianne Williamson for president” signs, buttons and stickers were still full at the end of the night.

More to Read

Get our Essential Politics newsletter

The latest news, analysis and insights from our politics team.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.