Gael García Bernal still remembers that rush of electricity he felt on the set of “Y Tu Mamá También” more than 20 years ago. Standing beside his friend and co-star Diego Luna, they took in the cameras and the crew, looked at each other, and knew: “This was it,” García Bernal said. “This was the point of no return.”

Call it hopeful naïveté, call it instinct or call it a kind of inheritance, but the two young actors, then just 19 and 20, were right. They were both on a cliff’s edge, right on the verge of international stardom.

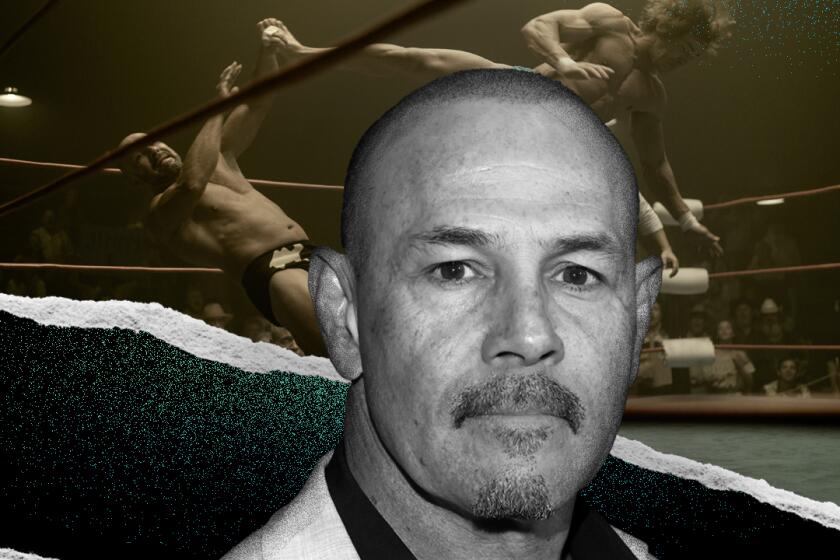

Saul Armendariz began his groundbreaking journey by overcoming homophobic taunts from crowds as an exotico, but now Cassandro is seen as a trailblazer and is the subject of a new Prime Video biopic.

Now, it’s a mild, sunny afternoon in early January — the thick of awards season — and García Bernal has only just flown back to L.A. when we meet at the London Hotel in West Hollywood. Aside from the salt-and-pepper streaks in his hair, the 45-year-old actor has retained the same boyish charm and mischievous glimmer in his hazel eyes that made him a standout all those years ago.

Born in Guadalajara, García Bernal came of age in Mexico City’s theater community. His parents, both actors themselves, had worked in television, but it was experimental theater that he says truly called to them. It was in that environment that he came to know Luna, whose parents were family friends.

“It was a really beautiful upbringing,” he said. And while he’d technically made his acting debut as a one-year-old, and starred in telenovelas throughout his teens, he spent a lot of his youth resisting the urge to pursue it more seriously.

“Why? Because it was there,” he laughed. He wanted to do something that was completely his own, and film became exactly what he was looking for.

From his feature debut in Alejandro González Iñárritu’s “Amores Perros,” García Bernal has operated on instinct, seeking out roles that have earned him praise in his native Mexico, as well as abroad, with an Ariel Award, a Golden Globe and two BAFTA nominations under his belt.

In his most recent film, Amazon Studios’ ”Cassandro,” he’s a hurricane of charisma, lighting up the screen as Saúl Armendáriz, the real-life wrestler who transformed lucha libre as Cassandro — the sport’s first openly gay exótico.

Though he jokes now that as a Mexican actor, playing a luchador was inevitable, he hadn’t given the idea much thought until director Roger Ross Williams sought him out. García Bernal was interested. He’d grown up loving lucha libre, but the script wasn’t finished. As time went on, the project became more and more real, and so did the idea of becoming Cassandro.

“He’s not just an ordinary luchador,” he said. “He’s campy and full of life. He’s pure exuberance.”

Kali Uchis discusses pregnancy, breaking industry barriers and new Spanish-language album ‘Orquídeas’

Kali Uchis is pregnant. The Grammy-winning artist discusses becoming mother—literally—and how she pen palled with Latin music’s biggest stars to make her new album “Orquideas.”

In the ring, outfitted in spangled Spandex unitards, García Bernal is electric. Out of the ring, he’s just as impossible to look away from, even as he grapples with the pain of the men who leave him because he won’t live life quietly. It’s a career-best performance that’s relentlessly joyful — something that was crucial for García Bernal and Ross Williams to capture.

“It would be easy to say that Saul invented Cassandro in order to find himself,” he said. “But he came up with Cassandro to confront the mythology of his father. Without knowing it, that’s what he was doing, and that’s what liberated him.”

Produced in part by La Corriente del Golfo, the production company García Bernal co-founded with Luna, the film speaks directly to their goals of creating art that transcends borders. The duo, along with their contemporaries and frequent collaborators, Mexican directors Iñárritu and Alfonso Cuarón, occupy a curious place in Hollywood.

They’ve done commercial blockbusters and indies, they’ve won critical acclaim at home and in America and as they’ve moved between these spaces, they’ve noticed some clear differences.

In Mexico, García Bernal says, films can be oblique, they can embrace ambiguity and contradiction without feeling obligated to explain them. In Hollywood, things are different. Here, films are more focused on clear narratives, ones that draw sharp lines between point A and point B.

Another glaring difference, one he’s hoping is beginning to change, is the lack of Mexican American films. A few years ago, when he served on a jury at Sundance, he remembers being struck by the fact that there wasn’t a single Mexican American or American Latino filmmaker on the lineup.

In hindsight, he has a hypothesis as to why: “It’s because they’re very well-behaved.” He’s partially joking, but there’s truth to it, too.

Even as a Mexican actor, he’s had American interviewers ask him to answer questions about the country’s anti-immigrant policies, or about racist remarks from American politicians. “It’s so unfair and so ridiculous to fall into that narrative,” he said. “That’s the most toxic thing you can ever do, is defend what you are not all the time.”

He wants Mexicans and Mexican Americans to embrace each other, to push each other and make great things. But he’s sympathetic to the different problems they each face.

“From the time you’re a little kid in America, you’re brought up in this kind of scary system of ‘If you do this, your future could be at stake,’” he said. “But to make good films, you have to take risks, you have to say things that nobody wants to hear, you have to behave badly, and I invite Mexican Americans to behave badly because we have so much to learn from each other.”

When he was younger, the actor explains, he struck up a friendship with the celebrated Mexican novelist, Carlos Fuentes. “It’s strange, no? To think of an older person, an intellectual befriending a young actor,” he said. “But he became a sort of mentor.”

When they would get together to talk about the state of things, the actor remembers that Fuentes would always make his way back to one core truth: “We have to make films, we have to write books, Gael. If not, this whole country falls apart. The whole meaning of life falls apart. We have to keep going.”

To tell the story of the famous Von Erick family, the filmmakers of “The Iron Claw” tapped Guerrero, the scion of another legendary wrestling family.

For García Bernal, filmmaking should be vital. His filmography is peppered with roles that have stoked controversy and sparked discourse about a whole host of cultural norms and taboos from masculinity to religion, or depictions of violence and sex. When asked if that was intentional, if he was always seeking out projects that might poke the bear, he chuckles.

“At a certain point, I think it was,” he said. “Films about taboos can fail miserably as well. But cinema, like poetry, has a way of reaching out into places where normal discourse doesn’t go. It requires a lot of dedication and rigor, though. It requires intention.”

Earlier this month, the actor’s visit to the Criterion Closet made waves when he plucked “Y Tu Mamá También” off the shelf and asked: “I want you to tell me which film has made you horny in the last years?” Online commenters clearly agreed with the sentiment, and when asked about it he demurred slightly at first.

“I was making a strong generalization,” he said. But after a few moments of scratching his brain for possible contenders, he winds his way back to his original assertion. “I can’t think of any since then that have that same sexual complexity. It’s so open and free and fun. It’s sexy, but it’s deep [in] the way that it challenges stereotypes and plays with them with humor.”

It’s partially the culture now, he thinks, alluding to the debates we’re currently having about the legitimacy of sex scenes or how we portray sexuality. He sees some of those impulses as a little prudish but does acknowledge that sex scenes can fall into the same trap of existing just for the sake of shock factor.

Either way, he said, what’s missing from cinema isn’t the sex itself, but the earnestness of “Y Tu Mamá,” something that initially caused Mexican critics to pan it as a superficial teen comedy.

“I love that history proved them wrong,” he said. “There’s an innocence, an openness there, and Alfonso Cuarón approached it with so much tenderness.”

For many American Latinos, the film is a gateway into Mexican and Latin American cinema — a portal into a world that presented characters, stories and whole histories that were, and still are, rarely seen in Hollywood. Throughout his career, it’s those roles, the ones that have stood the test of time, that have crossed borders, that have informed the way the actor looks at success.

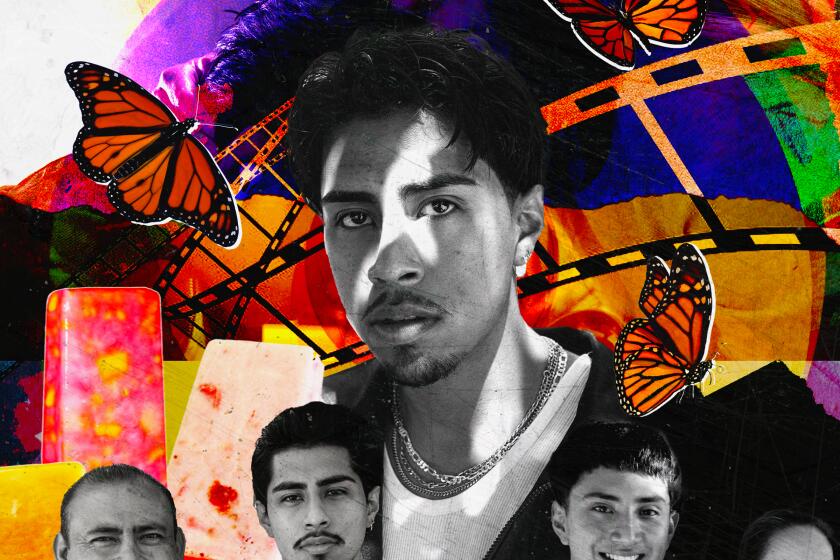

A DACA recipient from a humble background, Ezekiel Pacheco’s story bears a striking resemblance to that of Nico, his character in ‘At the Gates.’

To him, a nomination from the Academy would be “fantastic,” because he knows it could be the reason that someone learns about Mexican films, or takes a chance on a Spanish-language story. But at the same time, he’s not in this for the recognition. Just hearing that someone has been impacted by one of his films is more than enough.

“For me, it feels like everything makes sense,” he said. “Hearing that you made someone’s world bigger — it’s possibly the nicest thing you can ever experience as an actor, but also one of the nicest things you can give to someone.”

It’s something that perhaps only an actor so well-versed in moving between borders, between cultures, between experiences, could capture so well.

“When language meets its end, and our ideas about identity fall away,” he said. “Art transcends.”

Cat Cardenas is a Latina writer and photographer based in Austin. Her work has appeared in Rolling Stone, New York Magazine, Harper’s Bazaar, GQ and other publications.