In the crowded race for D.A., who can break out of the pack to challenge George Gascón?

The candidates vying to become L.A. County’s next district attorney could barely fit on stage together for a debate.

Scrunched into a dozen studio chairs that left political foes and ideological opposites inches apart at the Waldorf Astoria Beverly Hills, the largest field of contenders ever to run for the office spent close to an hour slogging through opening statements. The candidates — mostly longtime judges and prosecutors — challenging Dist. Atty. George Gascón cried out for microphone time, which they mainly used to deliver messages as similar as their resumes.

Former federal prosecutor Jeff Chemerinsky said his “No. 1 priority is public safety.” Deputy Dist. Atty. Jonathan Hatami is running to “make sure your children are safe.” L.A. County Superior Court Judge Debra Archuleta asked if voters were “safer now than they were three years ago.”

Between the packed stage and a feisty crowd that occasionally interrupted the discussion, the Feb. 8 event left little room for substantive policy discussion.

In some ways, the forum reflected the state of the race: crowded, chaotic and confusing for voters. Recent polls indicate many Angelenos are fed up with Gascón and anxious about crime, yet two-thirds of voters remain undecided in the March primary, according to a recent USC/Dornsife poll.

Though Gascón is likely to glide into the general election, observers believe he is vulnerable in November. But the tight pack has made it hard for a true threat to emerge, with no challengers rising above single digits in polls.

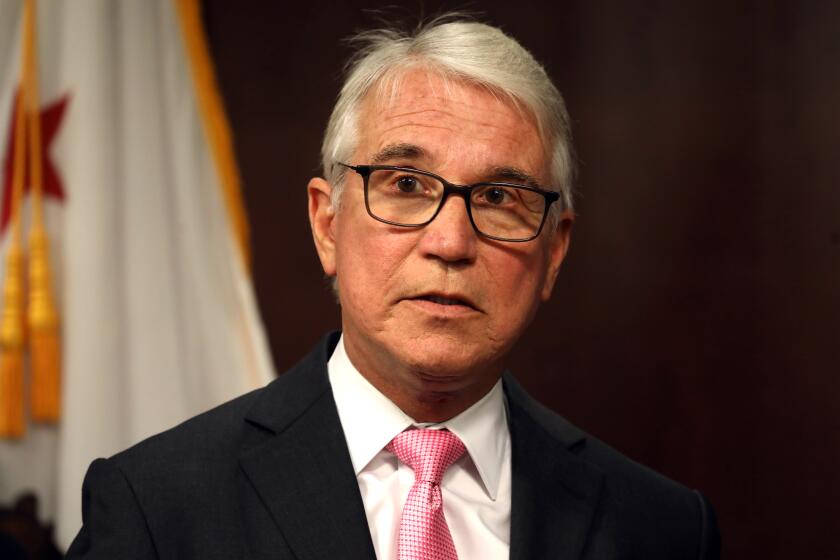

L.A. County Dist. Atty. George Gascón sailed into office in 2020 during a nationwide push for criminal justice reform. Now a large field is running to deny him a second term.

“I think a lot of the other candidates smell blood in the water, hence they are hopping in this thing just to see what would happen,” said political consultant Brian Van Riper, who is not involved in the race. “The interesting question is: How do they pop through?”

Nearly all of the 11 challengers want to roll back some or all of Gascón’s restrictions on the use of the death penalty, sentencing enhancements and prosecuting juveniles as adults. The test is to find a way to stand out not from the district attorney but one another — without pulling too far right of an increasingly progressive L.A. electorate.

Standing head and shoulders above the pack in fundraising is Nathan Hochman, the onetime Republican candidate for state attorney general who is now running as an independent to “get politics out” of the D.A.’s office. Hochman has raised well over $1.5 million and bought television advertisements that often prove key in communicating with L.A. County’s more than 5 million registered voters.

Hochman is a longtime federal prosecutor and defense attorney who once served as president of the Los Angeles City Ethics Commission, and his fundraising prowess could prove pivotal in a November matchup with Gascón, who pulled in $12.4 million when he ousted Jackie Lacey in 2020.

Arguing that he’s been miscast as the conservative in the race, Hochman described his politics as “socially moderate” and his approach to criminal justice as “the hard middle.”

He said his approach requires figuring out “who the true threats are to public safety and have to go to jail, and quite honestly the ones that aren’t.” A first time, nonviolent offender, he said, “still has to be held accountable for their actions, but community service or diversion might be the play.”

Hochman wears his defense background as a mark of distinction in a race against many experienced prosecutors. He has called for expanded use of mental health and drug courts to push lower level offenders into treatment, but has also made aggressive prosecution of fentanyl dealers a hallmark of his campaign message.

Hochman bristles at any suggestion that he’s too conservative for L.A.’s electorate. He says he’s never voted for Donald Trump, but he sometimes talks about crime in apocalyptic terms that echo right-wing criticisms of California, frequently comparing L.A. to “Gotham City.” He has accused Gascón of ushering in “the golden age of criminals.”

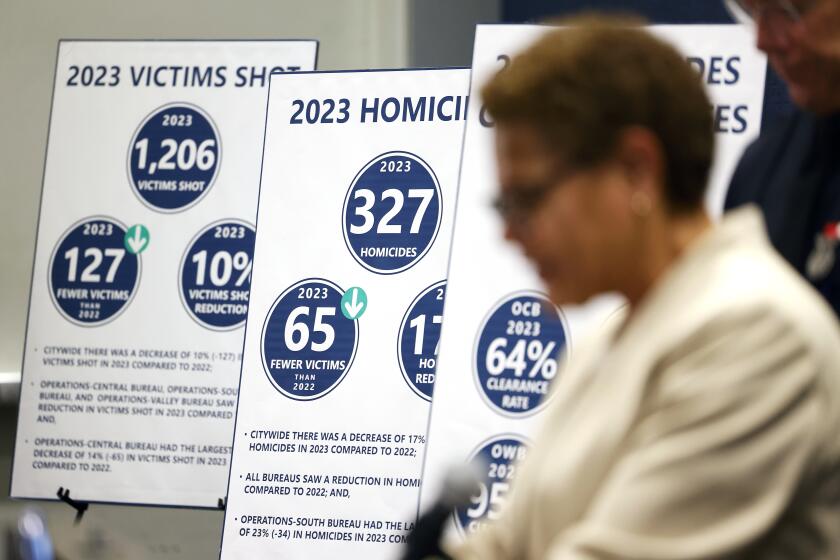

Los Angeles city and police leaders on Wednesday pointed to a 17% drop in 2023 homicides compared with the year before, but the bright spot comes with caveats.

Gerard Marcil, a Republican mega-donor who pumped significant funds into campaigns to recall Gov. Gavin Newsom and Gascón, has given a quarter of a million dollars to a committee supporting Hochman. Hochman‘s campaign has also paid more than $100,000 to the Pluvious Group, a Republican firm that organized Trump fundraisers in 2020.

“My campaign employs a bipartisan mix of Democrat and Republican fundraisers, which reflects the independent approach that I’ll bring to the D.A.’s office. Criminals don’t ask for your party registration when they rob you,” said Hochman, who estimates half of his major donors are Democrats or independents.

Rival candidates have been quick to try to paint Hochman as incapable of beating Gascón one on one.

During a January debate, Deputy Dist. Atty. Eric Siddall referenced Hochman’s 2022 loss to Rob Bonta in the attorney general election. “There is no way in God’s green earth that he is going to beat George Gascón in a general election,” Siddall said.

In 2020, Gascón swept into office on a raft of endorsements from national Democrats after a summer of protests demanding criminal justice reform. But his first term has been marked by legal battles with his own prosecutors, two failed recall bids and controversial decisions that have led opponents to blame him for acts of violence. Some of his reform policies were blocked by a judge early in his term.

Polls show voter anxieties about crime are surging, and several polls indicate more than 50% of voters have an unfavorable view of Gascón’s job performance.

Van Riper, the political consultant, said such a low rating can be a political “death sentence” in a competitive race. “People typically don’t change their minds about who they don’t like,” he said.

Gascón scoffed at the polling during a recent interview.

“During my campaign in 2020, I was polling around 27%. I got 54% of the vote,” he said. “The reality is the poll that counts is the one on election day.”

The field, the incumbent D.A. said, has failed to make any substantive “policy argument” to voters beyond a promise to erase his tenure.

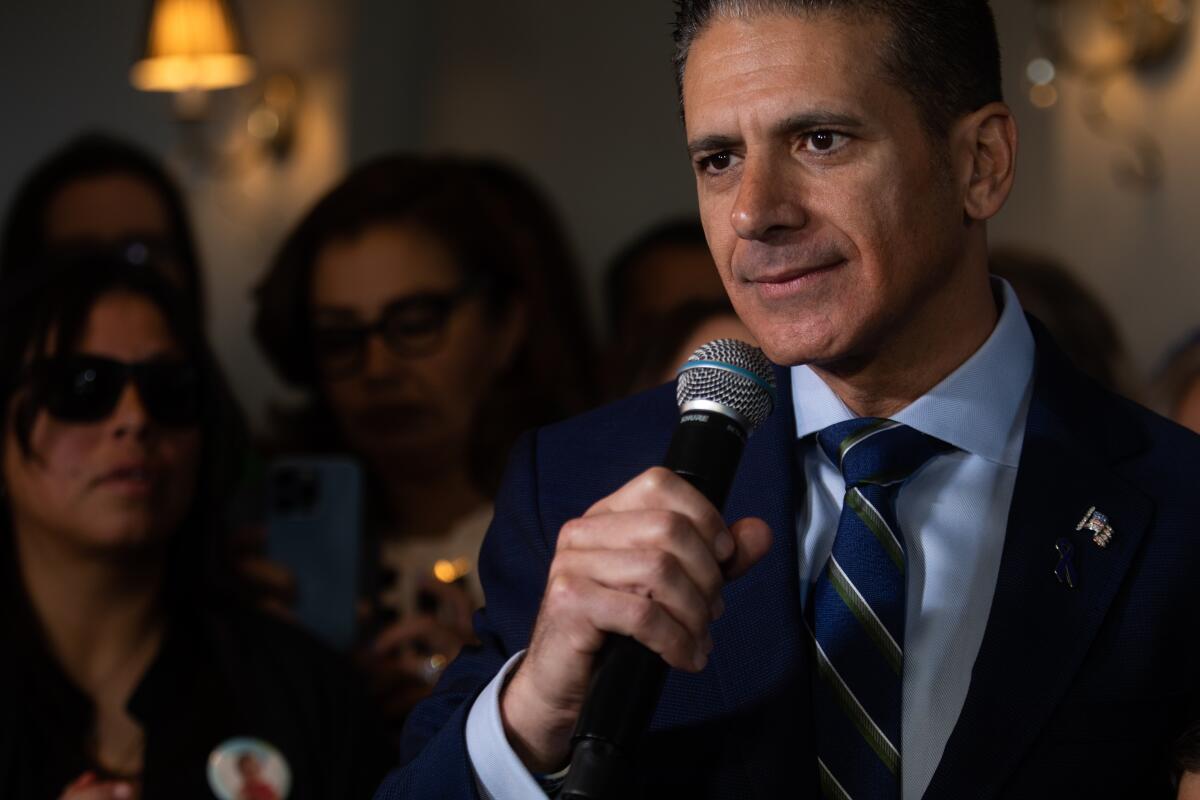

Of the four members of Gascón’s office in the race, Hatami might have the best chance of unseating his boss. The USC poll placed Hatami in second in the primary, with support from 8% of voters compared with Gascón’s 15%. Hochman was third with 4%, and no other candidate garnered more than 2% support.

Hatami is one of only three candidates to raise over half a million dollars in the race and has been a thorn in Gascón’s side, frequently challenging the D.A. on TV and elsewhere in public. A longtime prosecutor of crimes against children, he is best known for winning convictions in the gruesome torture murders of Anthony Avalos and Gabriel Fernandez. He has built up a base of crime victims frustrated with what they perceive as leniency from Gascón.

“I think sometimes when you vote for a D.A. it’s not just policies, I think people want a leader,” he said. “I think people want someone who is going to fight for them.”

L.A. County D.A. to pay $5 million in civil rights case over bungled election conspiracy prosecution

The district attorney’s office has settled a lawsuit filed by a small Michigan tech firm over a 2022 prosecution that was largely based on the word of conspiracy theorists who questioned the results of the 2020 presidential election.

Promising to govern “with a heart,” Hatami has promised to be flexible on some public safety issues: He says most juveniles should not be tried as adults and rejects the idea of prosecuting in a way in which every defendant “is getting slammed with the most severe punishment.”

Hatami allied himself with conservative talk radio host Larry Elder and former Sheriff Alex Villanueva during the recall campaigns against Gascón, which could turn off some general election voters.

“I don’t run from them or hide from them,” Hatami said of those connections. “I’ve joined forces with a lot of people that I don’t politically agree with.”

At a recent debate, when asked to rate how safe he felt in L.A. County on a scale of 1 to 10, Hatami said “zero.”

In L.A. County, violent and property crime are up roughly 8% from 2019 to 2022, according to California Department of Justice data. Criminologists say it is disingenuous to solely blame, or credit, crime trends on a district attorney’s policies. LAPD records show homicides and robberies trending down in recent years.

That’s the kind of nuance Chemerinsky hopes will carry him to the November ballot. The most progressive of Gascón’s top challengers — with a war chest second only to Hochman’s — the former federal prosecutor is hoping to scoop up Angelenos unhappy with the incumbent but squeamish about an overcorrection that would erase reforms they demanded four years ago.

“I believe strongly in criminal justice reform,” he said. “I think we need reform at each and every stage of the process.”

Chemerinsky says he would undo all of Gascón’s initial policies except for his ban on the use of the death penalty. Like Hatami, he says he believes that “juveniles should be treated as juveniles” outside of extreme cases, but rejects Gascón’s initial blanket ban on seeking to try some teens as adults. (Gascón retreated from his absolutist policy on juveniles in 2022.)

But Chemerinsky is more measured on the use of sentencing enhancements in gang crimes. In an interview, he noted flaws in law enforcement databases tracking gang members, and said that the use of such enhancements should be carefully considered.

“I think [gang enhancements] have been abused in a couple of ways. ... Are we talking about actual gang-related conduct as opposed to a gang-related individual?” he asked.

Giovanni Hernandez and Miguel Solorio were both convicted of murders they said they had nothing to do with as teenagers. Their efforts to be exonerated finally came to fruition on Wednesday.

Comments like that have opened Chemerinsky up to attack. Siddall labeled him “mini-Gascón,” and other critics have noted his father, legal scholar Erwin Chemerinsky, was on Gascón’s transition team in 2020. The elder Chemerinsky says he had no hand in drafting Gascón’s policies.

Also running as a moderate but struggling to match Chemerinsky in fundraising, Siddall has taken up the role of attack dog in the race, labeling Hochman as too right-leaning and Chemerinsky as a Gascón sequel.

Claiming to represent a “new generation of prosecutors,” Siddall rejects the death penalty and wants to refocus the office on prosecuting what he believes to be the true drivers of violent crime — gang leaders and enforcers, as well as those who organize “smash and grab” retail thefts.

But he thinks others in the field are giving unrealistic assessments of crime in L.A.

“I think it is overblown to say that we live in Gotham,” he said. “The idea that we’re at a zero [safety level] is absurd and it doesn’t bear out in reality.”

With less than three weeks before the primary, the rest of the field is fighting for air and tends to echo itself.

Archuleta and Deputy Dist. Atty. Maria Ramirez have both struggled to raise money. While Ramirez has cast herself as a steady hand whose wealth of management experience can restore confidence in the office, Archuleta has leaned heavily into concerns about public safety and dismissed statistics that show crime is down.

Deputy Dist. Atty. John McKinney is the longtime major-crimes prosecutor who convicted Nipsey Hussle’s killer in 2022, but it’s unclear how his record of trial success helps him stand out in a field replete with courtroom veterans.

Gregory Black, accused of killing three in a crash, had been released two years ago after a murder case was roiled by revelations a detective had bugged a lockup.

Superior Court Judge Craig Mitchell, founder of the Skid Row Running Club, says he is uniquely qualified to help tackle L.A.’s spiraling homelessness crisis. Another judge, David Milton, frequently champions the death penalty and has proudly invoked his Republican bona fides in a county where most registered voters are Democrats and independents.

Dan Kapelovitz, a defense attorney running to Gascón’s left, refers to the rest of the field as “mass incarcerators,” but has spent more time on debate stages making jokes than offering policy solutions.

The last to enter the race was a cold case prosecutor named Lloyd “Bobcat” Masson, who says his focus on property crime and made-for-prime-time moniker will give him a boost with voters who find themselves dazed and confused by the long list of alternatives.

“Each candidate saw there was no one coalescing, and for different reasons they all thought they could do it better,” he said of the primary.

Masson sounds confident for a complete unknown in the race. But after 10 challengers threw their hat into the ring, he figured, why not him, too?

“If it’s a party, I’m coming,” he said.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.