Like the assassination of President Kennedy in the United States, the 1994 slaying of Luis Donaldo Colosio — a charismatic presidential candidate who vowed to reform Mexico’s historically autocratic political culture — has long generated doubts and conspiracy theories.

Many Mexicans have rejected the official finding that a lone gunman, Mario Aburto Martínez, a seemingly nonpolitical factory worker, was solely responsible for the shooting death of Colosio during a campaign rally in the border city of Tijuana.

The killing has generated tens of thousands of pages of testimony from hundreds of witnesses, along with books, documentaries, a TV mini-series and endless debate highlighting widespread mistrust of Mexico’s legal system.

Now, with Mexico embarking upon another national election year — and with the 30th anniversary of the Colosio assassination approaching — the incendiary case, and all its polemical parts, have been thrust back into the political scrum.

On Tuesday, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador rejected a petition to pardon Aburto, who has spent almost 30 years in prison for the crime.

“I can’t do it,” López Obrador said of the pardon during his regular morning news conference.

The assassination, the president explained, was “a matter of the state” that should continue to be investigated.

With the ruling party nomination, López Obrador protege Claudia Sheinbaum is favored to be Mexico’s next president; she’s facing Sen. Xóchitl Gálvez.

The pardon entreaty might have been dismissed out of hand had it not been for its initiator — Luis Donaldo Colosio Riojas, son and namesake of the slain candidate. On Monday, Colosio Riojas told reporters that it was time to “turn the page” on the contentious matter.

A pardon, Colosio Riojas declared, would “permit both my family and Mexico to heal … to begin to take a road toward reconciliation.”

Colosio Riojas is an up-and-coming lawmaker whose name carries tremendous weight. He’s 38 years old and mayor of the northern city of Monterrey, a bastion of opposition to the party of López Obrador. Colosio Riojas is also currently a senatorial candidate for an opposition party.

Critics of López Obrador see politics behind his actions. The president’s political movement, critics say, could benefit politically from an investigation implicating the former ruling party in the slaying of Colosio. López Obrador, a leftist, routinely denounces conservative political opponents who previously ruled Mexico as members of the “mafia of power.”

The president scoffed at the notion of any electoral motivations.

“I have no intention of using such a lamentable situation for political reasons,” said López Obrador.

At the time of his slaying, Colosio, as the standard-bearer of Mexico’s long-dominant Institutional Revolutionary Party (known as the PRI), was an overwhelming favorite to be elected as Mexico’s next president. After his death, the PRI named Ernesto Zedillo, who had been Colosio’s campaign manager, as the replacement candidate. Zedillo, a lackluster technocrat, was elected president.

Colosio’s killing has long prompted critiques rejecting the official finding that Aburto acted alone. Supposed culprits behind the slaying include Mexican government elements hostile to Colosio’s reformist agenda and drug cartel leaders worried about a prospective crackdown on their activities.

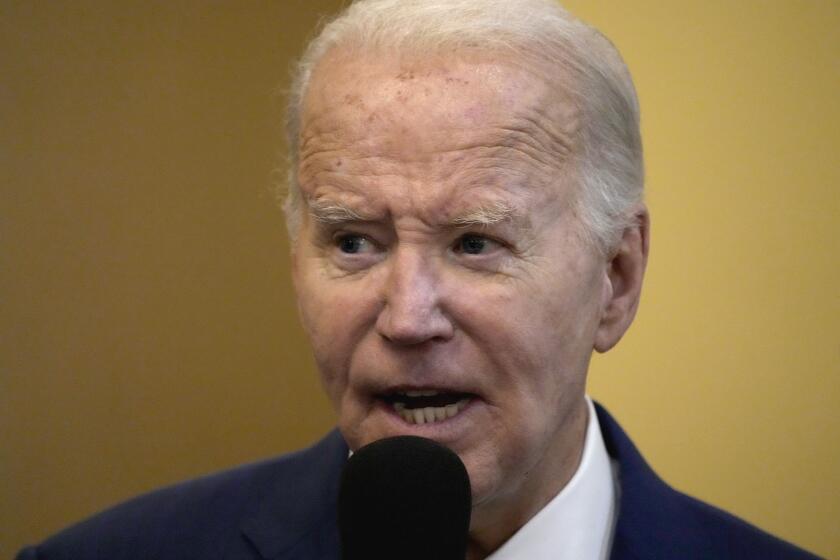

President Biden has said he’d shut the U.S.-Mexico border if given the ability. What does that mean?

President Biden has made some strong claims about shutting down the U.S.-Mexico border over the last few days.

Various alternate inquiries into the case have found that authorities mishandled leads, ignored evidence and generally botched the investigation. Aburto, the convicted killer, has asserted that he was tortured into confessing.

One widely circulated hypothesis is that the Aburto doing time is actually a doppelganger for the real assassin, who was supposedly killed after knocking off Colosio.

The case, wrote columnist Salvador García Soto in the Mexican daily El Universal, “never was totally resolved in the collective imagination, and, moreover, was manipulated to conceal the truth.”

The pardon issue arose just as the Colosio case has taken on a new investigative twist.

Mexico’s attorney general has publicly charged that a “second gunman” — a former Mexican government intelligence operative — was involved in the slaying.

For Kennedy assassination followers, the allegation inevitably brings to mind the purported second shooter on the “grassy knoll” in Dallas’ Dealey Plaza on Nov. 22, 1963.

In a news release Monday, the attorney general’s office said that the second-gunman suspect, identified only as Jorge Antonio “S,” a former government intelligence officer, was present at the assassination site in Tijuana’s Lomas Taurinas neighborhood in 1994 and was whisked from the scene. Blood found on his clothing matched that of Colosio, the attorney general said.

Moreover, the attorney general accused a federal judge of a “criminal cover-up” in blocking its inquiry into the second gunman.

On Tuesday, López Obrador said that the federal prosecutors’ allegation of a second gunman and a judicial cover-up should be investigated.

Breaking News

Get breaking news, investigations, analysis and more signature journalism from the Los Angeles Times in your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“It’s important that there is no impunity if this involves a crime, that, according to prosecutors, has some relation with an institution of the state,” the president said.

Colosio was shot twice — in the head and abdomen — during the rally in a district close to Tijuana’s airport. The killing immediately thrust Mexico into a deep political crisis when the government was already dealing with severe economic woes and the Zapatista rebel insurrection in the south.

The continued opaqueness of the Colosio case extends to the fate of Aburto, now 53. He was initially sentenced to 45 years in prison under federal law. But a judicial ruling last year stated that his sentence should have been 30 years, under state law in Baja California, where the assassination took place. If the 30-year sentence is applied, Aburto would be freed from prison in March.

However, the Mexican federal attorney general is appealing and seeking reinstatement of the original, 45-year prison term.

No matter what happens on the legal front, Mexico’s most sensational murder case in recent decades seems sure to continue to resonate in an election year in which voters are to choose a new president. And, as with the Kennedy assassination north of the border, many in Mexico will probably remain unconvinced that justice was done in the killing of Luis Donaldo Colosio.

Special correspondent Cecilia Sánchez Vidal contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.