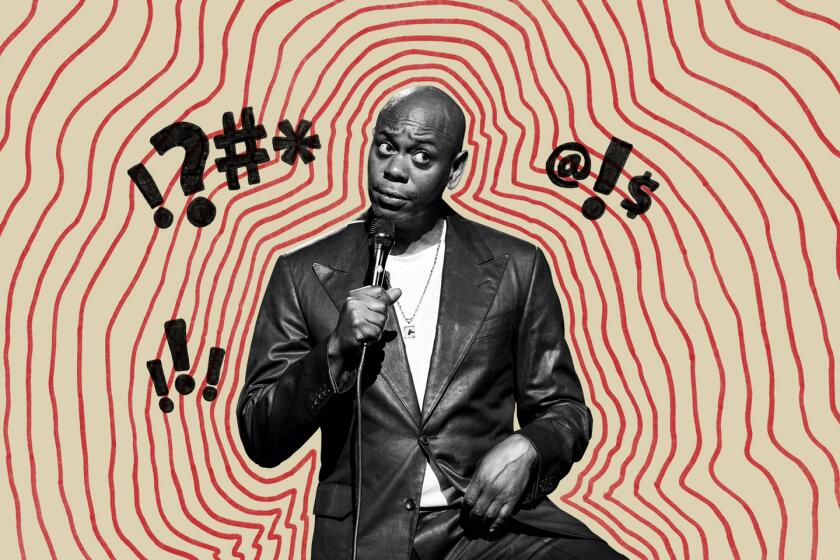

Rare photos of Dave Chappelle and Lenny Kravitz sparkle in Mathieu Bitton’s ode to Paris

It is a freezing cold Saturday night in West Hollywood, but it is sweltering hot inside the jampacked opening gala of renowned photographer, art director and designer Mathieu Bitton’s photo exhibition “Paris Blues: A Decade of Moments and Reflections,” on display at Leica Gallery Los Angeles. Outside, a line runs down the block with people waiting two hours to get into the star-studded event where Lenny Kravitz, Dave Chappelle and other famous folks including actor Jason Momoa, comedian Chris Rock and music producer and songwriter Jimmy Jam are all in attendance.

With images taken in Paris over the last 10 years, “Paris Blues” illustrates Bitton’s longing for his hometown through his unique lens, presenting photos that reflect his childhood, including an image of the building he grew up in and a photo of a crêperie, which Bitton titled “Barbe à Papa” as per his childhood obsession with children’s book character Barbapapa. The exhibition also features candid images of celebrities like Kravitz and Chappelle, reflecting the career Bitton carved out in the United States but which often brings him back to his roots in the City of Light.

Seated on the gallery’s patio during the week leading up to the exhibition, Bitton says “Paris Blues” feels like a diary of his life — whether it’s the images that pay tribute to his childhood or the celebrity photos. “People always say, ‘Oh, my God, you shoot these celebrities and that must be amazing,’ but I am there too, capturing them, experiencing the same moment from the other side,” he says.

Bitton, who lives in Malibu, returns to his homeland several times a year. In 2012, he was decorated with the title Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters) for his significant contributions to French culture, both nationally and abroad.

Much of Bitton’s artistry — with photos and beyond — has been inspired by music. He’s art-directed and designed over 1,000 albums for film soundtracks and famous acts including Jane’s Addiction, Dolly Parton and Stevie Wonder. His photography canon is an equally comprehensive who’s who of music including John Mayer, Bruce Springsteen and Wu-Tang Clan.

He also has long-standing tenures working closely with Kravitz and Chappelle. His work with the latter won him two Grammys as a producer on the comedian’s albums “The Closer” and “What’s in a Name?”

Originally, Bitton set out to do a music exhibition, but perhaps influenced by midlife introspection at 50 years old, he decided to make his photography show more personal. Combing through his archives, Bitton reviewed a whopping 30,000 photos that he’d taken in Paris over the last 10 years. He would pore over, cull, and edit photos from 7 a.m. until midnight every day until he finalized the exhibition’s 36 images.

He named the exhibition after one of his favorite movies, “Paris Blues” (1961), Just like the film the exhibit is named after, Bitton’s collection is composed of exclusively black-and-white images. “They feel more timeless than color photos,” he says. So committed is Bitton to black-and-white photography, he shoots on a monochrome camera, and a manual one at that. Noting the time it requires to focus the lens and the deliberateness behind each shot, he says, “It’s not just a digital snapshot. It’s not just something where I’m like, boom, and I get lucky that it’s an incredible perspective.”

To imbue the images with additional depth and a unique sheen, Bitton favors silver gelatin prints, which he says are costly but worth the investment due to their “museum-like quality.”

“There is something very individualized about Mathieu’s work,” says Leica Gallery Los Angeles Director Paris Chong. “His prints are so beautiful and unique, and he has such incredible artistic sensibilities.”

Despite his accolades, Bitton reveals “a horrible case of impostor syndrome” and says he struggles with seeing himself as an artist. Staring incredulously at his name printed in bold graphics across the gallery’s upper street-facing window, he says it’s “completely surreal” that it can be seen by passersby.

In the face of Bitton’s own unassuming self-image, perhaps reflected by a blurry self-portrait that he included in the exhibition, is a majestic picture he took of singer-songwriter Jorja Smith. Photographed from the neck upward, with half her face in shadow and the other half beautifully illuminated — the image, with its completely dark background, is so intriguing it draws one’s eyes deeper into it as if it’s somehow suspended in a never-ending dimension.

Beside it a vibrant picture of Mick Jagger, caught in the throes of laughter, practically leaps out of its frame. Shot at a posh, private hotel in Paris, Bitton’s photo captures the decadent setting and Jagger’s upscale fashion, but also the moment’s relatability, with the top of the rock star’s shirt unbuttoned and a huge smile spread across his face — demonstrating the humanity that defines the photographer’s images.

“When I see his work … what he photographs of our faces, our bodies, our posture ... our humanity comes beaming through,” writes Chappelle in the foreword of Bitton’s 2020 coffee table book “Darker Than Blue.” Noting the duality to Bitton’s photography — both human and epochal — Chappelle also writes, “Some of the most iconic images taken of me were captured by him.”

The exhibition’s photo of the comedian is no different. What could have been an ordinary moment of Chappelle smoking a cigarette while standing on a Paris street at night wearing an overcoat, hoodie, jeans and sneakers, became mythical as Bitton captured it, with snow falling all around Chappelle and powdering the ground.

Bitton’s savvy also extends to recognizing a moment’s significance — and paradoxically, sometimes even for what the moment is not. Hanging above the image of Chappelle is a captivating photo of Kravitz playing a trumpet during a sound check at a Paris concert hall in 2018. It is an anomalous photo of the rock star who, at the time, was learning how to play the instrument.

“Normally, somebody would expect, ‘You got a Lenny [Kravitz] photo, so it’s gonna be great fashion or rock ‘n’ roll with a guitar,’” Bitton says. “But this was an off-moment of Lenny learning something new. We already know the rock star, so this is a cool moment.”

“I love it,” Kravitz says over the phone, amid a flurry of awards season interviews. “It really captured a moment in my life where I was on the road and in my spare time I was working on something that I hadn’t had the time or hadn’t taken the time to work on.”

Bitton was 13 years old and visiting his mother, Mireille, who had relocated to Los Angeles for work (Bitton’s parents divorced when he was 7), when he first met Kravitz. His then-roommate, fashion designer Christopher Enuke, once worked as Bitton’s mother’s assistant, and became a big brother figure to Bitton. “There was a dude smoking weed on the couch, listening to Led Zeppelin and wearing a KISS T-shirt,” Bitton says. “And that was Lenny.”

Three years later, Bitton was awestruck by Kravitz’s 1989 debut album, “Let Love Rule.”

“I became obsessed with that record,” he says. “I was like, ‘I can’t believe I know this guy.’ I became a total fan.”

Fast forward two decades and it was Bitton who pitched to Kravitz the idea of releasing a 20th anniversary deluxe edition of “Let Love Rule,” and assumed multiple roles as the project’s art director, designer, editor and producer. He also wrote the liner notes. What’s more, Bitton has taken myriad photos of Kravitz, joined him on world tours and directed “Looking Back on Love,” a 2011 documentary about the making of Kravitz’s record “Black and White America.” He has worked on all of Kravitz’s music releases from 2009 onward, and did the art direction and design for Kravitz’s forthcoming album “Blue Electric Light.”

“Mathieu is family,” Kravitz says. “We’ve spent so much time together and I trust him as a human being to look out for my best interest and to put me in the best light possible. I also trust his point of view photographically … artistically.” What distinguishes Bitton’s photography, continues Kravitz, is that “it’s highly identifiable. There’s a soul. There’s grit. There’s depth … layers … and a composition that I always recognize immediately.”

The singularity of Bitton’s photos is illustrated by an amusing anecdote about a photo in the exhibition of a couple kissing passionately, titled “The Affair.” As Bitton relays the story, it sounds like a narrative from a French farce. When the lovers noticed they’d been photographed, they insisted that he delete the photo immediately. There would be trouble if their respective spouses were to see it. Ooh la la. Upon looking at the image on Bitton’s camera, however, the woman not only marveled at its beauty, but also requested a copy.

Bitton says he’s especially French when it comes to being a die-hard romantic. There are several photos of couples kissing in the exhibition. But it is the exhibition’s photo of a man smoking a cigar at a flea market and various images of children that exemplify what Bitton misses the most about Paris. “Whenever I see kids in Paris, it makes me want to be a kid in Paris again,“ he says. Growing up, Bitton spent Sundays at the Marché aux Puces Saint-Ouen de Clignancourt with his father, Raymond, an avid art collector who would spend all day long at the legendary flea market looking for treasures.

Just as his father immersed himself in art, Bitton has always immersed himself in music, with an affinity for jazz, funk, soul and the blues. A couple of his music idols are reflected by the names of his sons — Miles, age 24, named after Miles Davis, and 21-year-old Julien, a French variation of Julian “Cannonball” Adderley.

Fueled by dreams of working in the music industry, at 14 Bitton left Paris and moved in with his mother in Los Angeles, In his late teens, he began collecting albums, preserving rare soundtracks and bootlegs in plastic, in addition to Blaxploitation film posters (he has 1,700 in his collection), spending hours at the famed Tower Records and Tower Video on Sunset Boulevard.

Figuring that his best route into the music industry would be music journalism, he studied at Cal State Northridge before transferring to New York University, where he obtained his journalism degree. To make ends meet, however, he worked in graphic design.

But it was Bitton’s vast record collection and talent for design that sparked his professional path when he was 22 . PolyGram executive Harry Weinger reached out to Bitton and asked him to lend the record label his copy of a rare Blaxploitation soundtrack so the company could make a reissue. Bitton promptly asked if he could design the project — and so began his freelance working relationship with the record label, which in 1998 was folded into Universal Music Group, where Weinger is currently vice president of A&R.

At the time, Bitton was also photographing friends’ recording sessions, designing their albums and shooting their music videos.

In 2004, soon after crossing paths with acclaimed art director and Warner Music executive Jeff Ayeroff, Bitton added the label to his roster. Ayeroff also became his mentor.

Heading into the late aughts, Bitton was also working in fashion and managing recording artists until he heeded the advice of the legendary Quincy Jones, who is pictured in one of the exhibition’s photos along with Kravitz and Charles Aznavour. Jones urged Bitton to narrow his focus. “He said, ‘You’re doing too much. If you’re doing 10 things well, you could be doing three things that are amazing, but you don’t have the time to do those three things amazingly,’” Bitton says.

“I was actually calling myself a jack-of-all-trades for a long time,” he continues. “So when Quincy said that it was literally like Thor hit me with his hammer. I was like, ‘Oh, my God, yes, he’s right.’”

Looking around the bustling opening reception for the exhibition, which closes on March 4, Bitton is beaming. He has spent most of his life capturing others’ notable moments but pauses, for a moment, to appreciate his own. Though it’s framed around his nostalgia-induced blues, his exhibition shows, beyond a doubt, that Bitton will always have Paris. Standing still and smiling broadly, he says, “I’m happy.”

More to Read

It's a date

Get our L.A. Goes Out newsletter, with the week's best events, to help you explore and experience our city.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.