Sweeping new LAUSD policy to restrict charter school locations; advocates threaten to sue

The struggle between traditional and charter schools intensified Tuesday when a narrow Los Angeles school board majority passed a sweeping policy that will limit when charters can operate on district-owned campuses.

Access to public school campuses for charter schools is guaranteed under state law — and charter advocates immediately threatened to sue over the new restrictions.

The policy, passed 4 to 3, prohibits the new location of charters at an unspecified number of campuses with special space needs or programs. One early staff estimate put the number close to 350, but there’s uncertainty over how the policy will be interpreted. The school system has about 850 campuses, but advocates are concerned that charters could be pushed out of areas where they currently operate, making it difficult for them to remain viable.

Under the policy, district-operated campuses are exempt from new space-sharing arrangements when a school has a designated program to help Black students or when a school is among the most “fragile” because of low student achievement. Also exempt would be community schools — which incorporate services for the broader health, counseling and other needs of students and their families.

The school-board majority said the new rules would protect needed space beyond the normal allotments for classrooms, counselors, health staff and administrators — for example, rooms for tutoring, enrichment or parent centers. Such spaces had frequently been tabulated as unused or underutilized — and then made available to charters.

Board President Jackie Goldberg has repeatedly minimized the impact on existing charter schools that already have sharing arrangements.

“We are not trying to undo what has already happened,” Goldberg said Tuesday, “but to rationalize what we have as we go forward.”

A chaotic rollout of a new federal financial aid form is roiling high schools and upending college admissions, impeding students from filling out the all-important FAFSA form.

Charter advocates countered that the new policy is illegal on its face and likely to cause widespread harm to charters and the students they serve because ambiguities in the language could allow any charter to be targeted.

The new rules also discourage placing charters where they could disrupt traditional feeder-school patterns. Goldberg cited the example of a charter middle school located on a district-run elementary campus. The charter school, she suggested, would have an unfair advantage in recruiting those elementary students, undermining the local, district-run middle school.

In the current school year 52 independent charters operate on 50 campuses, according to L.A. Unified. The number is expected to be smaller for next year and down significantly from a peak of more than 100. But even 50 schools would make for one of the larger school systems in California.

In all, there are 221 district-authorized charters and 25 other local charters approved by the county or state, serving about 1 in 5 public school students within the boundaries of L.A. Unified — about 535,000 students total. Most charters operate in their own or leased private buildings.

The L.A. school system has more charters than any other district in the nation. Most were approved under charter-friendly school boards and under state laws — since changed — that made it difficult for school districts to reject charters.

The new policy is flawed, charter supporters said, because it presumes charters are entitled only to “leftovers,” space that the district has no need for after making use of whatever other rooms and areas a school or program would want.

The litigation argued that students suffered when the state closed its schools during the COVID-19 pandemic and that officials did far too little to help.

“By prioritizing public school students attending district-run schools over public school students who attend charter public schools, the policy violates” state law mandating that “public school facilities should be shared fairly among all public school pupils, including those in charter schools,” according to a letter sent to the district Monday by the law firm Latham & Watkins.

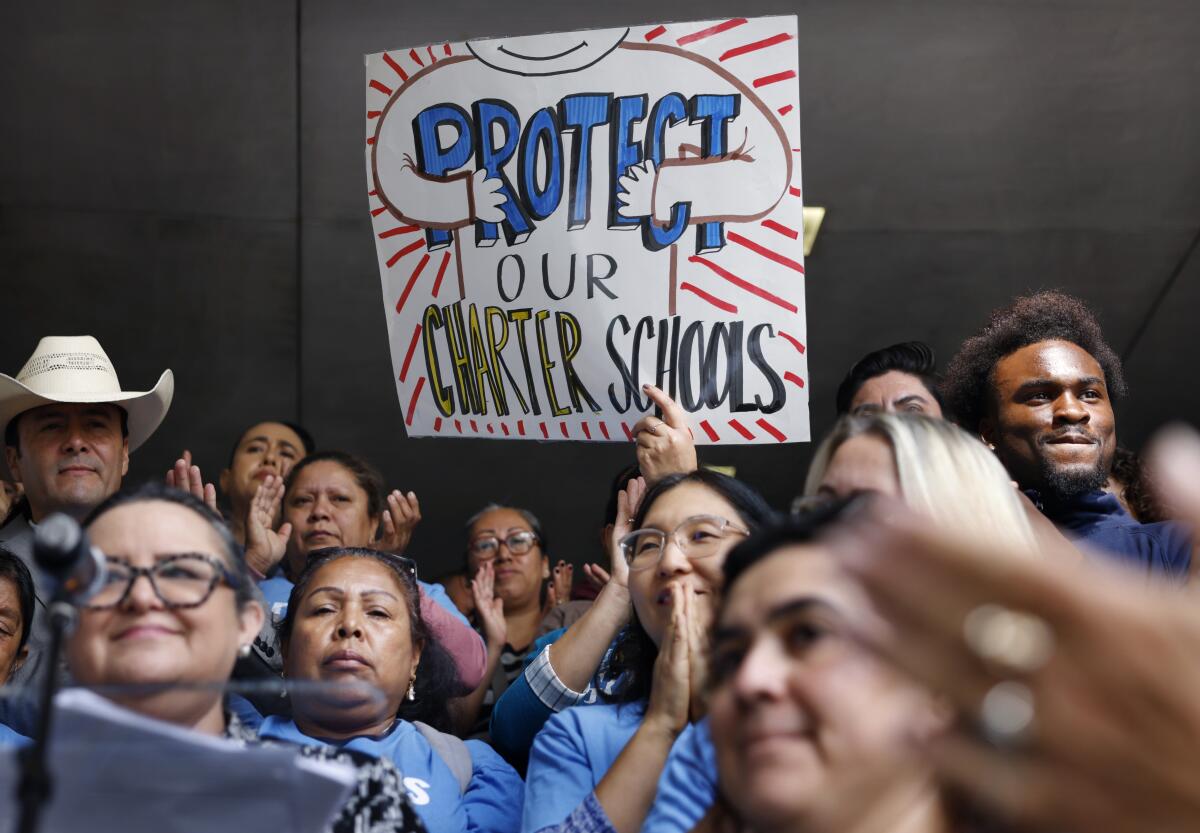

The passions on each side were expressed by parents and educators — who would have addressed the board by the dozens for hours were it not for a time limit on comments.

“When my son was in first grade, we got a call from Ararat Charter,” Gayane Ghardyan said. “And we felt like we won the lottery. My son entered as a low-level English learner.... He is now thriving. Protecting school choice is imperative, because a school that works for one student may not work for another.”

Ararat, an elementary school, has shared a campus with an L.A. Unified elementary school in Van Nuys for 13 years without major issues, said Aida Tatiossian, the charter’s founding principal.

But Alejandra Hernandez, a staff member at a community school, talked of how her campus, Bertrand Avenue Elementary in Reseda, offers an array of extra services that require space. Bertrand currently does not share space with a charter.

The school’s parent center provides English as a second language courses and the school also hosts a parent leadership academy, she said. There also are enrichment programs — outside of regular classes — in robotics and social studies and plans for expanded creative arts, mental health services and a food pantry.

Sharing a campus with a charter would mean “we lose our rooms and service and enrichment plans,” she said.

But her school’s potential dilemma raises a contradiction within the policy itself. Six charters that share LAUSD campus space are designated as “community schools” under a state program, according to the California Charter Schools Assn.

Under the new policy, would these charter schools be entitled to advantages over the vast majority of L.A. Unified campuses that are not community schools?

The split on the board mirrored political sympathies for charters on one side and for the teachers union on the other. United Teachers Los Angeles has strongly opposed most charters and favors stricter regulation. Most charters are nonunion.

The resolution that led to the new regulations was co-authored by Goldberg and Rocio Rivas. The new policy also was supported by George McKenna and Scott Schmerelson.

“This was one step forward,” Rivas said. “There’s still a lot more we have to do.”

All four have been supported in their campaigns by the teachers union.

Goldberg and McKenna are retiring and Schmerelson faces a tough reelection bid in the west San Fernando Valley — underscoring how the anti-charter leaning of the board majority will be at stake on the ballot in the March school board races.

“Many people believe that what this policy includes now is still not enough,” Schmerelson said. “I hear you.... But we have made progress and ... we will keep the conversation going.”

Voting no were Nick Melvoin, Kelly Gonez and Tanya Ortiz Franklin. All three have benefited from support from charter allies. Gonez also had teachers union support in her most recent campaign.

Of this group, only Franklin is on the March ballot.

The development of the new policy “wasted the time, effort and emotions of staff, advocates and the public,” Franklin said. “The policy doesn’t solve any of the real co-location challenges and gives false hope to its supporters.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.