U.S. revises ‘plant hardiness’ map for gardeners to keep pace with climate change

Southern staples like magnolia trees and camellias may now be able to grow without frost damage in once-frigid Boston.

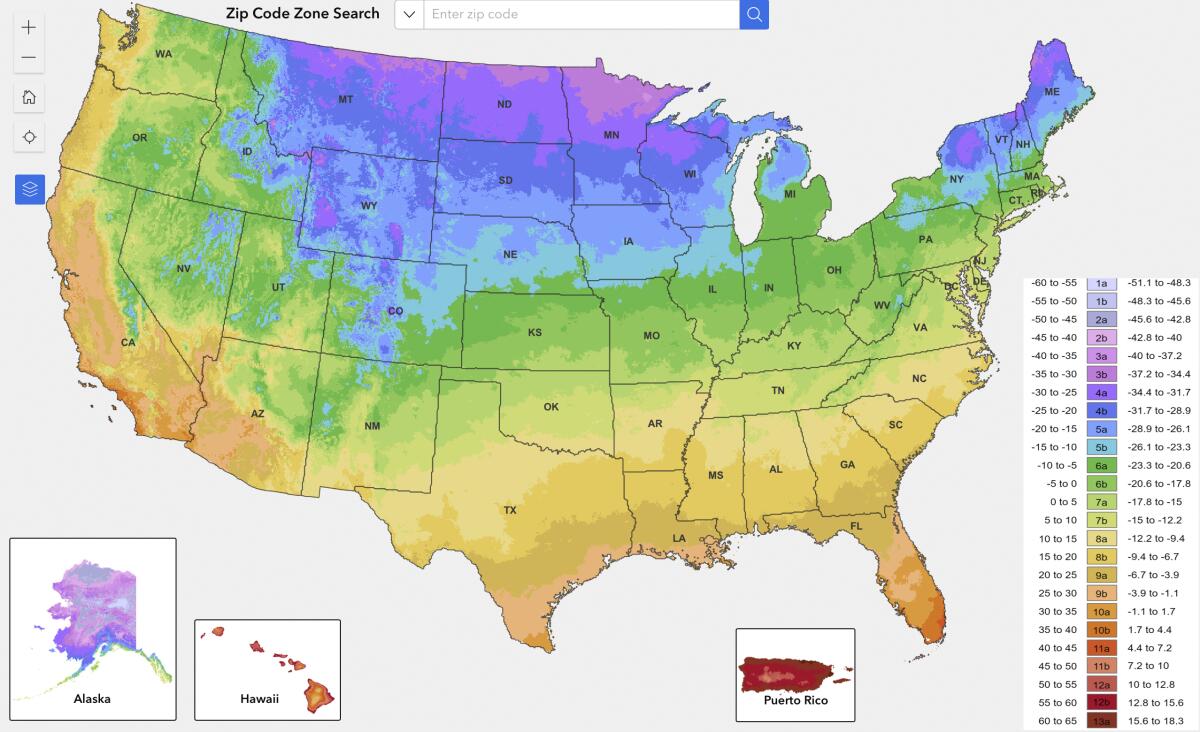

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Plant Hardiness Zone Map was updated Wednesday for the first time in a decade, and it shows

the effect that climate change will have on gardens and yards across the country.

Climate shifts aren’t even — the Midwest warmed more than the Southeast, for example. But the map will give new guidance to growers about which flowers, vegetables and shrubs are most likely to thrive in a particular region.

One key figure on the map is the lowest likely winter temperature in a given region, which is important for determining which plants may survive the season. It’s calculated by averaging the lowest winter temperatures of the last 30 years.

Across the lower 48 states, the lowest likely winter temperature overall is 2.5 degrees warmer than when the last map was published in 2012, according to Chris Daly, a researcher at Oregon State University’s PRISM Climate Group, which collaborates with the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service to produce the map.

Boston University plant ecologist Richard Primack, who was not involved in the map project, said: “Half the U.S. has shifted to a slightly warmer climatic zone than it was 10 years ago.”

He called it “a very striking finding.”

December is prime planting time for native plants in Los Angeles, and habitat restoration projects are looking for volunteers ... or is it the other way around?

Primack said he has noticed changes in his own garden: The fig trees are now surviving without extensive steps to protect them from winter cold.

He has also spotted camellias in a Boston botanical garden and southern magnolia trees surviving the last few winters without frost damage. These species are all generally associated with warmer, more southern climates.

Winter temperatures and nighttime temperatures are rising faster than daytime and summer temperatures, Primack said, which is why the lowest winter temperature is changing faster than the U.S. temperature overall.

As the climate shifts, it can be tricky for plants — and growers — to keep up.

“There are a lot of downsides to the warmer winter temperatures, too,” said Theresa Crimmins, who studies climate change and growing seasons at the University of Arizona and was not involved in creating the map. “When we don’t have as cold winter temperatures, we don’t have as severe die-backs of insects that carry diseases, like ticks and mosquitoes.”

She added that hotter, drier summers in some regions may kill plants that once thrived there.

“You wouldn’t want to plant plants that aren’t adapted right now for where you’re living,” she said.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.