In most of Ukraine, the days and nights are still soft and summer-clear, with only a faint tang of autumn in the air. But if Russia has its way, winter will come early.

Moscow’s signature strategy of the last cold-weather season is already being unleashed again this year, in the form of a thunderous barrage of strikes that Ukrainian officials said targeted electricity infrastructure in several parts of the country.

The Sept. 21 attacks, the first of their kind in six months, caused partial blackouts in half a dozen provinces, including in the capital region. It was an ominous sign of things to come — and a reminder of hardships past.

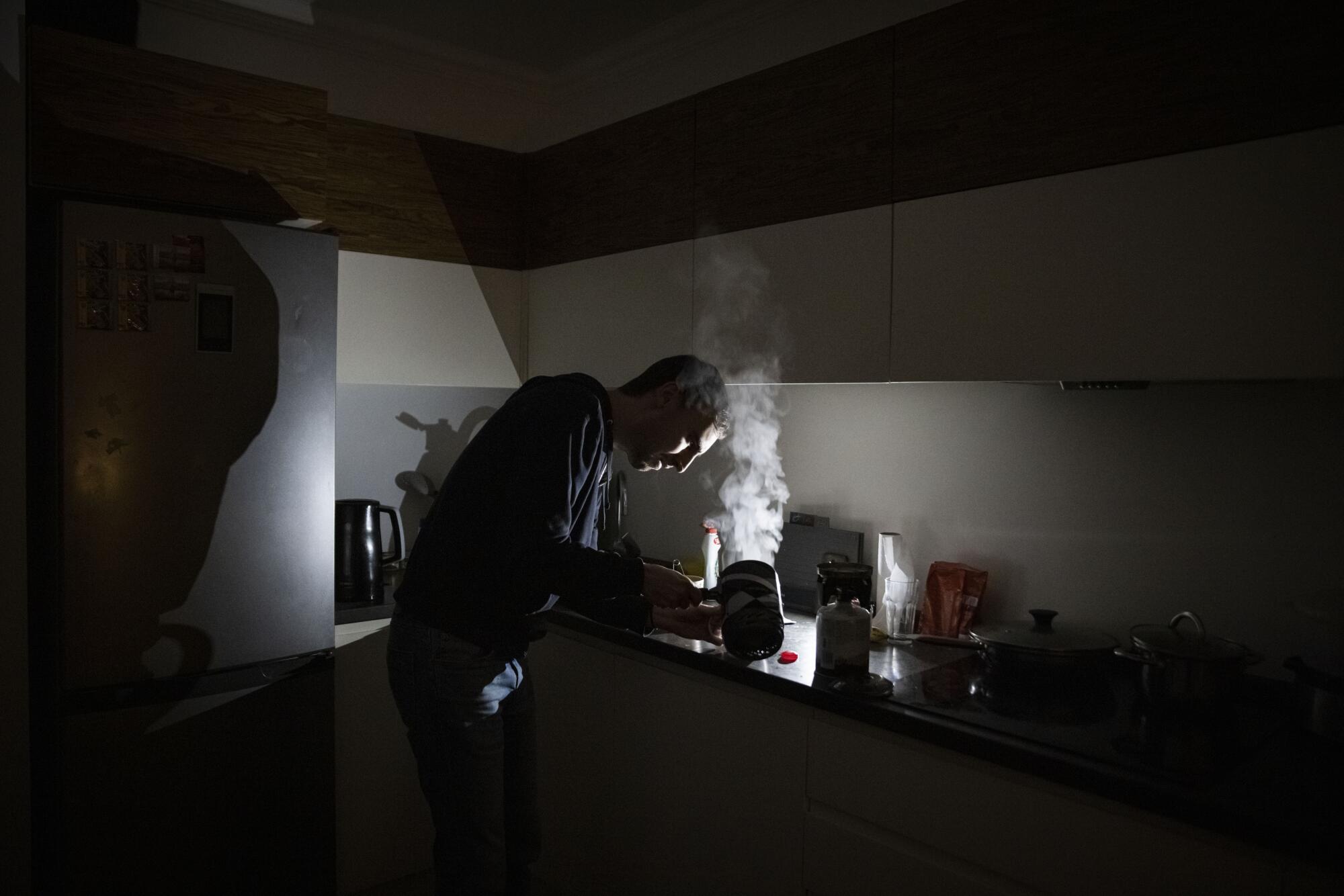

Virtually every Ukrainian family has stories to tell about power-related privations last winter: major metropolises and tiny hamlets alike plunged into inky blackness; the run on generators and candles; the painstaking scheduling of daily activities — cooking, shopping, bathing — around pre-timed power cuts meant to preserve the grid.

“I remember just standing at the bottom of all those flights of stairs in despair — very pregnant, my arms full of groceries,” said 37-year-old Iulia Statnyk, a Kyiv photographer who lived in a 20th-floor apartment last winter. This year, she and her husband, together with their 10-month-old baby, have settled in a house equipped with a generator.

Rolling blackouts protect the bomb-damaged power grid in the Ukrainian capital. Residents shrug off the inconvenience.

Hoping to avoid a repeat of last winter, Ukraine has rushed to protect and harden its power grid, although for security reasons, officials are circumspect about some of the particular measures being taken.

President Volodymyr Zelensky, in a U.S. television interview in mid-September, warned Russia that if last winter’s pattern of hitting electricity infrastructure resumes, Ukraine would consider retaliation in kind to be fair play.

Over the last year, Ukraine has demonstrated that it can mount drone attacks deep inside Russia, including in Moscow, though Zelensky’s government does not formally acknowledge responsibility for such strikes.

“If you cut off our power, deprive us of electricity, deprive us of water, deprive us of gasoline, you need to know we have the right to do it,” Zelensky told CBS’ “60 Minutes.” But even if it wanted to, Ukraine does not have the capacity to hammer Russian civilian power infrastructure as thoroughly and systematically as Moscow’s forces did here.

We know that this winter, they will try again to break us.

— Yuri Herasko, working on Ukraine’s electrical grid

Ukraine described last winter’s attacks on the electric grid as an attempt to break people’s spirits and freeze the country into submission, but in many instances, the hardships fostered a sense of community.

In high-rise apartment buildings in Kyiv and elsewhere, neighbors banded together to leave emergency provisions in elevators in case people were trapped by unexpected outages: water, snacks, diapers.

Even so, many view the prospect of a fresh season of prolonged outages with dread. February, in all its freezing gloom, will mark the second anniversary of what has become a grinding conflict with no clear end in sight.

How do citizens of Kyiv cope with the sleep deprivation and stress from Russia’s war on Ukraine? Some push it down, some try yoga or dancing.

Last winter’s waves of drone and missile strikes ultimately affected about half the Ukrainian energy sector, taking aim at power substations, hulking transformers and other key electricity infrastructure.

At one point last winter, Kyiv’s mayor, Vitaly Klitschko, even mused about the possibility of a mass evacuation if the power cuts made it impossible to provide running water. A Russian talk-show host expressed a fervent longing to see the Ukrainian capital drowning in raw sewage.

Amid those punishing strikes, Ukraine scrambled to stay ahead of mounting damage, with repair crews working around the clock and under fire, desperately jury-rigging old equipment and rationing precious power.

Along the way, electric crews gained the status of folk heroes, with people often calling out praise and encouragement when they see even ordinary repairs taking place.

“You can tell what we are doing is appreciated,” said Mykola Marmur, a 44-year-old power worker from Mariupol, a southern city that was captured by Russia early in the war after having been nearly leveled by fighting.

Working on a recent day on the outskirts of Kyiv with a crew from DTEK, the country’s largest private power distributor, Marmur said safeguarding the power grid was a point of national pride.

“I hope I can do this for my own city someday soon,” he said.

Even some of Kyiv’s close allies have grumbled that it doesn’t seem sufficiently grateful for the aid it’s received. How thankful is thankful enough?

Ukraine’s drive to repair last winter’s damage and shore up safety has been helped along by an infusion of Western support, including $375 million worth of electricity-related aid from the United States.

In early summer, the country’s energy minister, Herman Galushchenko, called it the “most extensive repair campaign in the history of energy facilities.”

One chilling aspect of Russia’s power-targeting airstrikes is that much of Ukraine’s energy infrastructure dates back to Soviet times, before the country attained independence in 1991.

Many of last winter’s most damaging attacks appeared precision-aimed at critical infrastructure like substations; the state-owned power distributor Ukrenergo said 70% of those were struck at least twice last winter. Some were hit again almost as soon as they were brought back online.

But the intensity of the attacks carried a bit of unexpected blowback: The strikes helped galvanize Western partners to shore up Ukraine’s air defenses. Even so, air defense remains a critical need heading into the winter — a precariousness that Zelensky stressed during a Washington visit in September and in recent talks with visiting European officials.

Weeks after Russian occupation, rural areas outside Ukraine’s capital still yield forest graves. Exhumations remain a near-daily task for police.

Russian atrocities number in the tens of thousands, Ukraine says. The ICC wants to arrest Putin. But what are the prospects for justice?

In the capital region, the last punishing winter came only months after Russian forces’ occupation early in the war of several bedroom communities close to Kyiv, including Bucha, whose name became synonymous with wanton killings and torture of civilians.

Russian forces broke off their attempt to seize Kyiv itself in April 2022, but combat and deliberate vandalism by the occupiers left behind massive damage to the electrical grid, presenting power workers with their first big challenge of the war.

In a span of only a month and a half, they managed to restore some 6,000 miles of power lines and more than 70 high-voltage substations in the Kyiv region, said Maksym Timchenko, the chief executive of DTEK.

The coming winter, he said in a statement to The Times, “will be no less challenging than the previous one.”

In a Ukrainian city devastated by bombing, the seasons of Jewish life find expression. Amid the sorrow of war, Rosh Hashana brings hope, even joy.

In the drive to prepare for winter, there have been some missteps.

In an August report, the Atlantic Council cited slow delivery of large autotransformers, and reports that a large shipment of American energy-related assistance included some equipment incompatible with Ukraine’s grid.

On a recent day, in a fast-food parking lot beside a roaring multi-lane road, a DTEK crew was busy drilling through cement to reach buried high-voltage lines that needed refurbishing.

This Ukrainian artist was known for whimsical sculptures. Now, amid Russia’s war on Ukraine, he creates art from war debris, military weapons and fury.

“We know that this winter, they will try again to break us,” said the crew’s supervisor, 48-year-old Yuri Herasko. “To be ready for all kinds of difficult scenarios — that’s our job, and we’re working just as hard as we can.”

In Kyiv and elsewhere, people hoped for the best, but prepared for the worst.

Generators are again in demand, and where best to procure diesel fuel for them is a hot topic. Country dwellers assemble stacks of firewood, and people dig deep in junk drawers for flashlights and batteries.

“You would not believe the collection of candles I assembled,” said Statnyk, the Kyiv photographer. “Every color and every scent — watermelon, apple, like 40 different kinds. Now we will just have to see what this winter will be like.”

Even far from Ukraine’s front lines, military funerals set off waves of mourning. ‘You can’t see an end to it,’ one chaplain says as the war drags on.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.