In this Mexican city, some girls dream about a crown made of vanilla.

Papantla adorns its Corpus Christi festival reinas, or queens, with the vanilla orchid’s thick brown stems woven, twisted and bejeweled into aromatic crowns — a nod to the spice’s place in the town’s history.

Centuries ago, the Totonac people here used the orchid Vanilla planifolia as a perfume; then the conquering Aztecs started mixing it into a chocolate drink in the time of Emperor Moctezuma. After the Spanish invaded, Mexico’s vanilla spread overseas and Papantla gained international fame.

In Papantla, Mexico, once a major vanilla-producing city, the spice is still strongly tied to people’s identity.

Mexico may no longer be the leader of the global vanilla trade — that’s Madagascar — but in Papantla, the spice still reigns.

Many of the city’s former reinas still prize their braided vanilla crowns decades later. The crown is a sweet memory infused with their youth, their city and their heritage.

“You can have a crown with many things — diamonds, emeralds, pearls,” said Marichu Mondragon, who won hers in 1981, “but a crown of vanilla only here.”

Marichu Mondragon, 59

Queen: 1981

1

2

1. Marichu Mondragon’s vanilla crown from 1981. 2. “The smell of the vanilla when they put the crown on you, I don’t know, it’s something that stays with you,” says Mondragon, 59.

Marichu Mondragon occasionally takes the jewels off her crown, bathes it in vanilla extract and leaves it in the sun for several days. The crown’s vanilla braids absorb the extract, she explains, keeping it like new.

Mondragon wears the crown every year at a celebration held by Pemex, Mexico’s state-owned oil company and her husband’s employer. She also brings it out for any Papantla event she’s invited to as a former queen.

Children across Mexico grow up learning the voladores ritual, where they fly around a 100-foot tree.

“The smell of the vanilla when they put the crown on you, I don’t know, it’s something that stays with you,” said Mondragon, who remembers being crowned by the first lady of Veracruz state.

Delia Nuñez, 94

Queen: 1949

1

2

1. Delia Nuñez, 94, poses for a portrait with her vanilla crown and scepter. 2. Nuñez shows a photograph from 1949.

Delia Nuñez was 19 and a schoolteacher when she competed for the vanilla crown. Her supporters for the Carnival of Papantla held a bullfight to help her win votes and to collect money for a new kindergarten where she would teach.

Years later, when she was raising her seven children, she would take her crown out of its storage place — a cookie tin in her closet — and hold it for them to smell.

Delia Nuñez, energetic and upbeat while struggling with memory issues, still has the crown, now dried and damaged. At her daughter’s home in Papantla, she put it on and smiled as she posed for a picture. She then sat down and looked through a photo album from when she was a teacher, before she won the money for the kindergarten the crown helped build.

Tania Zayas, 27

Queen: 2014

Tania Zayas didn’t want to be queen.

But her high school pressed so hard for her to be its candidate in the Corpus Christi festival that the then-17-year-old gave in.

“I was embarrassed,” said Zayas, who now teaches physical education at a Papantla elementary school.

She now doesn’t shy away when people seek her out as a former queen. Her crown is woven in the shape of a pyramid representing the nearby El Tajín archaeological site. It also contains two orchids and three hearts, a symbol of the region.

“Once I did it and was on the other side, I said it’s really an experience that all women should have,” she said. “It’s more lovely because you stay in the history of Papantla.”

Alma Rosa González Herrera, 85

Queen: 1958

Alma Rosa González Herrera was 18, working as an accountant and living with her parents in 1958 when several ranchers came to their home one afternoon asking if she would run as their candidate for queen of the Corpus Christi festival.

González, who had already been a “student queen” at her high school the year before, was pleased but not overwhelmed.

“Those things almost don’t move me,” she said. “I was contributing to my town.”

But González, who married a rancher and today writes poems for a local newspaper, has saved the crown for more than half a century. A photograph at her home in Papantla shows the then-teenager smiling, her hair covered in the confetti a crowd tossed in the air when she arrived at a theater for her coronation.

Josefa Vargas Riaño, 71

Queen: 1972

1

2

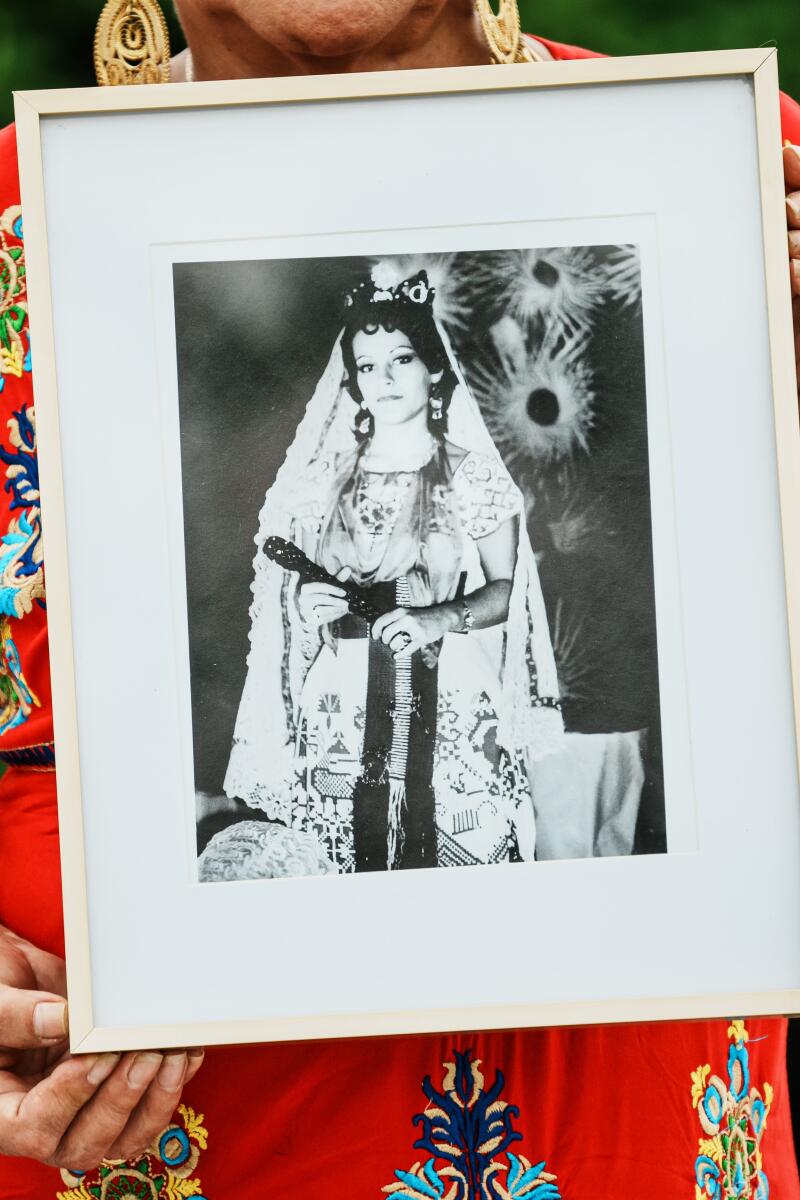

1. Josefa Vargas Riaño, 71, poses with the crown and wand she won at 19. 2. Vargas Riaño holds a framed photo of herself as queen in 1972.

The race for Josefa Vargas Riaño to become queen of the Corpus Christi festival was simple. Vargas, then 19, and two other candidates for what she called “the biggest party of the city” drew envelopes from a crystal bowl. Vargas was stunned when she saw that hers said “queen.”

Photographs of her coronation hang on the wall at Freijoó Casa Vintage, the hotel she owns in Papantla, which will soon have an exhibit about the history of the queens.

“This was a really nice part of my youth,” said Vargas, who also works for Pemex.

This shrimp in vanilla sauce recipe is one of various dishes infused with the spice at Nakú, a restaurant in Papantla, Mexico.

On the 50th anniversary of Vargas’ coronation, about two dozen former queens gathered to help celebrate.

“Many congratulations for all the honor you have given us during these last 50 years,” the mayor said. “A queen or princess of Corpus Christi officially serves for only one year. Even after she gives up the crown, in reality, never, never, does she stop being a member of the royal court.”

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.